The Landscape Library speaks with, Diane Lipovsky and Stacy Passmore, principles and co-founders of Superbloom, a woman-owned landscape architecture firm in Colorado.

Hear how their passion for restorative regenerative landscapes is complimented by their expertise infusing ecological and social systems throughout their designs.

In this episode we talk about a plethora of projects including Superbloom’s 1881 Heritage Farm Park, which won the 2022 Jeff Harner Award for Contemporary architecture.

We also talk about unique aspects of landscape design, such as the value of research and local collaboration, the benefits of modeling, the use of model materials like clay, wood and cork.

How did Superbloom start?

Diane Lipovsky:

Stacy and I met at another firm here in Denver and we initially got started over a campfire.

But we just found working together on several projects that we had a lot of alignment in kind of our goals for our work and for our landscape architecture generally.

We really wanted to fuse ecological systems with social systems and make really cool visionary designs with a lot of interest in research and getting our hands dirty while we make really cool drawings to come up with ideas for what we imagine future conditions to be.

Before the interview, you mentioned Superbloom started during the pandemic. What was starting a business like in the pandemic?

Stacy Passsmore:

Well, we actually decided to do it before the pandemic and then once we had it in our minds that this is what we wanted, I think we weren’t going to turn back.

Diane Lipovsky:

Yeah, it was interesting, like people had different reactions. Some people thought it was bold, or terrifying, while others thought it was the best time, when things are down, they’ll go back up.

I think the workplace element of remote work has added complications, but we were able to spend a lot of time really honing in on our mission and the kind of work we want to do, and it seems like that has really resonated with people, with clients, with people who want to work with us.

We’ve had a really exciting year and we’ve taken on some projects that really just exceed our expectations as far as the perfect projects to work on.

Did you start Superbloom with one typology of landscape in mind to pursue?

Stacy Passmore:

We did. It was something that was really important to us. But probably the pandemic for sure, with clients and people choosing to improve their landscapes, it does seem like an interest in connecting back with food systems and being thinking more long term about the health of the land that has taken on a heightened importance.

Diane Lipovsky:

I mean, maybe for lack of a more eloquent thing, I think a lot of people watch a lot of Netflix and there’s a lot more documentaries about some of the things that are really important to us and a lot more kinds of information available or maybe people able to sit down and listen to it.

Stacy and I talk all the time about how it’s crazy that in the last 10 years how much more interested clients are in the kind of edible food systems and how their small little plot of land relates to larger ecological systems.

Stacy Passmore:

The kind of niche that we are, was an opportunity that we saw was that there’s a lot of firms or people that are like really strong on like the social systems and there’s a lot of firms that are really strong on the ecological systems and that like we feel like they are synthesized, and they should be synthesized, and you know, it’s sometimes difficult. There’s the dynamics of farms or living with these active landscapes. It just takes like a different way of approaching the project, which is also kind of like back to the research component that is so interesting to us.

How important is research to your company and also to the landscape field?

Stacy Passmore:

For us it’s like the starting point and in a way, related to why we wanted to craft our own practice.

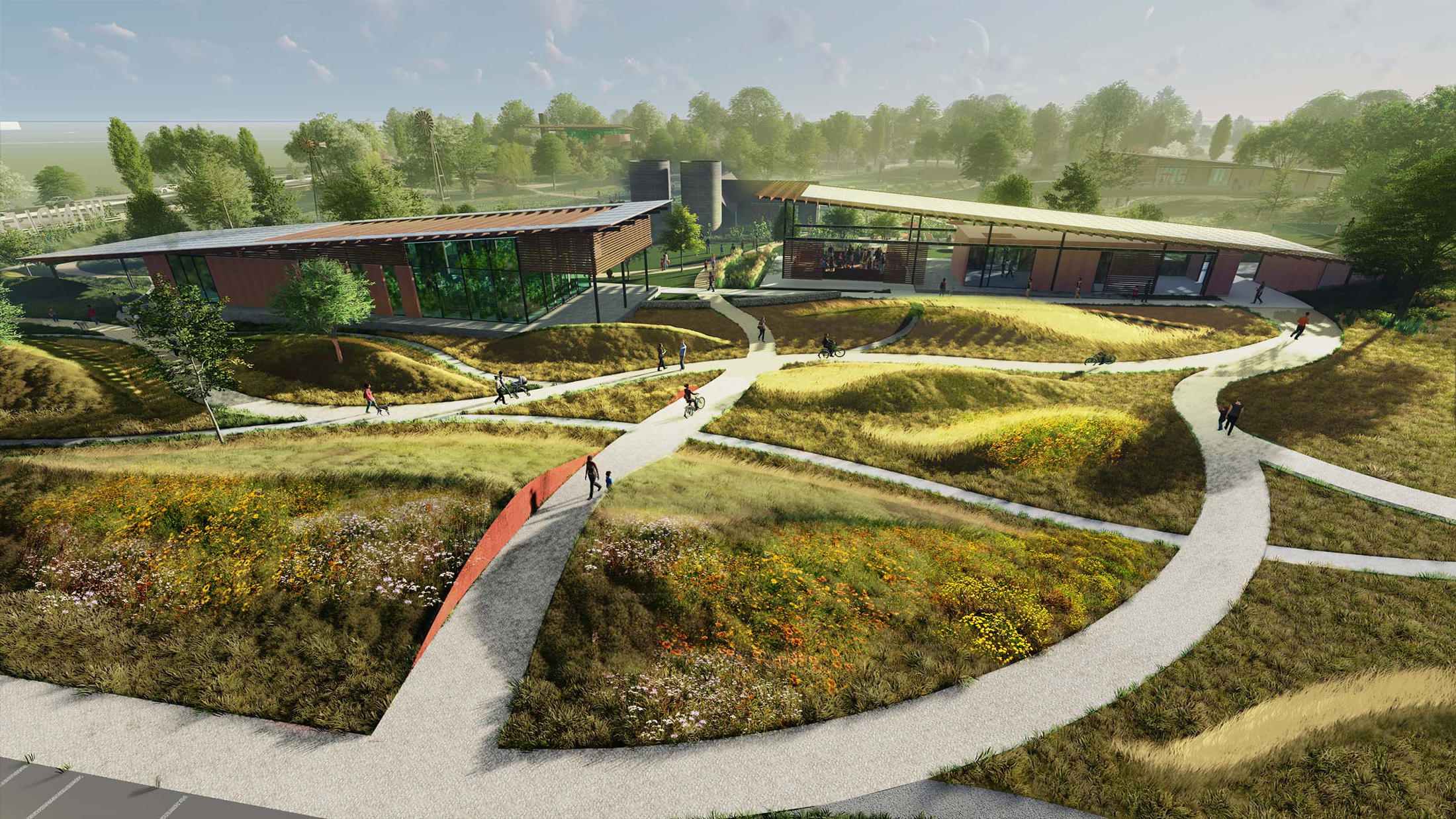

For example, we’re working on this park called “1881 Heritage Farm Park” right now and it’s a 15-acre park. It has an existing historic homestead located at the site, but the intention is not to kind of create this museum of the past but to really celebrate and to explore the future of agriculture and the future of growing food in the west here in eastern Colorado, which is obviously like a very specific environment.

And during that project, we really started by talking to people and contacting everyone from people at the historic society in the museum in the city of Aurora to people at the University of Colorado who are experts in soil science or dry land farming.

We spoke to people at the Botanic Garden trying to capture as many different kinds of systems or angles that might apply to the project, bringing that into the design and letting it inform the actual formal decisions about space.

Diane Lipovsky:

We also look at research as a multi-scaler operation, just like we see design in that way.

1881 Heritage Farm Park is a big park, and we convinced our client that it was really important that we engage with the local expertise on the number of different issues.

You know, even for a residential project, we’re working on a regenerative orchard in the South Denver area, and we wanted to get our own hands dirty and test the soil and really get in there and look at it with even more granularity.

We engaged with a orchardist on the best most desert adapted fruit species and you know, really trying to build that in and, and trying to also include in our, in our work like manuals for the research that we’ve done so that not only does the owner have this book of like, we’ve tested your soil, we’ve looked at all these different tree species, we’ve done all this work so that they have that to share, we have that to share with our future clients.

Is each project unique in research, or do you build off information from project to project?

Stacy Passmore:

Definitely some of both. Some of the knowledge applies to other projects like, you know, we also work quite a bit in the mountains of Colorado on more restorative projects that are larger scale meadow restorations or river systems.

Those projects can be more easily applied across the sites. But definitely each project is different, between objectives and sites.

Diane Lipovsky:

For example, the residential regenerative orchard project, we definitely used the research that we did into drought tolerant fruit species into that farm park.

I think something that we’ve really enjoyed, or at least I’ve really enjoyed about starting our business is kind of creating our West Anderson dream team of collaborators like our orchardist that we brought into our “1881 Heritage Farm Park” project. It’s cool to see what we’re all building, kind of library of knowledge on some of these really interesting ideas and design practices.

What was the research like on the project "Under One Roof"?

Stacy Passmore:

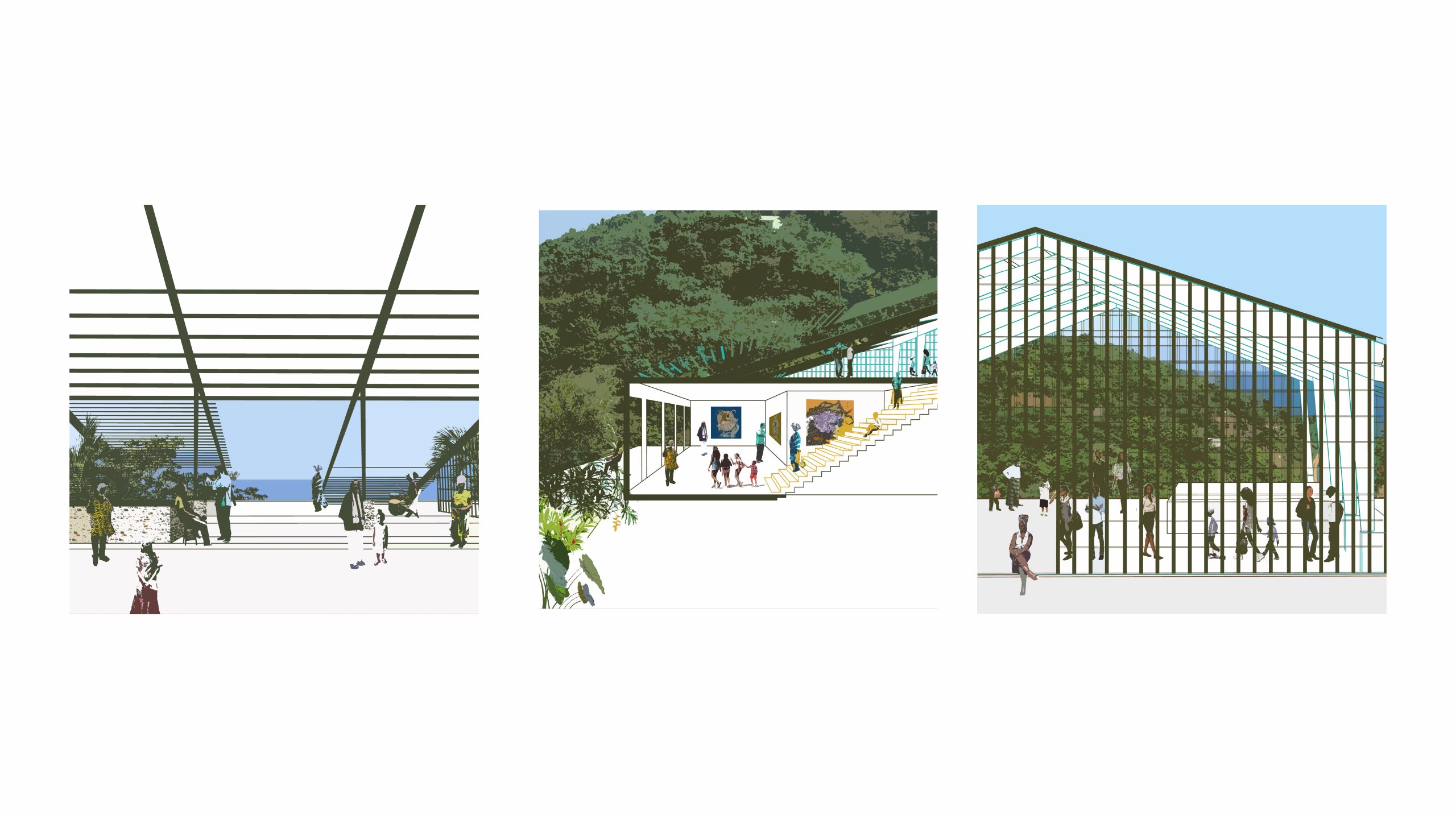

Under One Roof was a master’s research project that I did while studying at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. This project is set on St. Thomas Island in the Virgin Islands, and it was a response to hurricanes that occurred there in 2017.

There were two hurricanes that basically destroyed everything on the islands. We were working with a local farmer’s market that had an existing structure and the project was to create a vision for rebuilding that then, then to create documents and drawings that they could submit to FEMA to then get funding to rebuild the farmer’s market.

So that particular project, because it’s an island ecosystem and very remote, the project really started with materials and this idea of the life cycle of design.

This project aimed at what could be available on the island itself and created a project that was really self-sufficient and required as few inputs as possible.

That turned into a couple different primary design decisions. One was creating a terrace of architecture farm and the terracing included these substantial water systems because there’s really no groundwater on these islands due to the volcanic nature of the geology.

All the water that they use for drinking comes from rainfall. So, designing this enormous roof that would capture water, store it in these cisterns and then the structure of the cisterns also created a kind of architecture for more productive space as well.

Growing food in the field that connected back to the farmer’s market and then creating spaces for people to actually make things of value from farmed products. So, taking what they had, which was this more or less basic farmer’s market and really turning it into like a larger community center and kind of like a beacon on the hill that also nestles into nature of the design creates spaces for people to come if there was a future hurricane.

Do you make architecture models for all projects?

Stacy Passmore:

We do, yeah. We are especially interested in experimenting with different materials depending on the project.

For the 1881 Heritage Farm Park, it’s in the prairie. So, we made some models with clay and some parts of our topographic design process was taking clay and then testing different kinds of prairie waves and mounds and typographies.

The Under One Roof model is made out of plywood but also cork. The cork was cut on a different CNC router that has a little blade. So, it was a stacked cork model and cork is like for landscape, just an amazing material to use because of the granularity of the kind of visual texture and use CNC machines to also build terrain in Rhino that then we would like CNC route, which is like the easiest and most amazing way to make a terrain model.

Diane Lipovsky:

We like to use models as a way not only to represent the final product but to inform the design.

We have a project called Cloud Bosque in Castle Rock that we, you know, do dirty study models. Just print what we’ve have, get all the push pins and just whatever we’ve got to just lift it up the model and look at it. The different angles from that to the kind of final kind of beautiful, finished product I think is something that’s fun for us.

Something we wanted to do more of when we started our own practice was to get our hands dirty on things other than the computer, you know, get outside more.

Beyond models we try to do field work Fridays, where we get outside and either study a site that we’re working on or some other site that we think will be important for illuminating the work we do.

When you're out in the field, what are three major things to look for when you're doing research and field noting?

Diane Lipovsky:

Good question. At least for me, something I’m always more conscious of when I’m outside is the detail.

Whether it’s the climatic condition, do I feel really dry, is it windy? You sense with all of your senses more intensely when you’re outside in the field as opposed to sitting at your desk thinking about what it would feel like to be there.

Stacy Passmore:

Yeah, Diane mentioned the kind of multi scaler, it’s that one to one, like being at the site, you know obviously we have so many amazing tools and technologies that allow us to study and see things from above, but you know, sometimes we’ll make up different kind of games or like processes, methodologies for ourselves. For example, this time we’re going to do sketches and study a particular thing or take drone photos, or simple as going to walk in this particular way.

You can have fun with it too. It doesn’t have to be the science or the technical side of it, but how does it feel and how can you have that experience and draw out like different types of experiences from being there?

Diane Lipovsky:

I mentioned that we are doing study models, and for the Cloud Bosque at Castle Rock, it’s on this elevated site and you know, you can do a half-acre in so many different ways.

We had so many different cool ideas and we were drawing in our studio and then at some point we were like, we have to go back out there.

So, we went back out to the site and just stood there for like five minutes and we didn’t really say anything, and we just looked out and listen and felt and heard and realized that the very coolest thing about the site is not the magnificent view of the mountains, which is really cool but is also something you can get in Colorado in a lot of places.

But the clouds, they felt so close to you because you were so elevated. So, we made the whole project hinge on opening and closing views to clouds, and it really worked in the educational landscape of clouds and Colorado.

We worked with a meteorologist here to develop educational signage about it. So that crystallized what the final design ended up being.

Have you ever done a one-to-one scaled model?

Diane Lipovsky & Stacy Passmore:

We do, yeah, we don’t have a giant office, so we don’t build everything at one-to-one scale. We have to question, how big is that going to be?

Even when you print something that’s supposed to be eight and a half by 11, you’re doing it in the computer and it looks great and then you punch it out and you’re like, oh my god. That’s enormous.

So, you're, you're not building 20-foot structures in your office?

Diane Lipovsky & Stacy Passmore:

*Laughs* No, that’s a future goal.

If there's one thing that you can think of to improve the landscape field, what would it be?

Stacy Passmore:

So many things. You will appreciate this. We would love to have a better way of modeling and drawing two dimensions and three dimensions together.

There’s the whole two-dimensional aspect of documentation and the tradition of the field, but then everything we do in landscape is like three dimensional. So, we have different softwares that we use for that, and we haven’t found anything that really brings them together.

There are just always these different steps. We have it down, one of the first things we do is always bring something into Rhino, because everything we do is so three dimensional. But then yeah, it feels like we’re duplicating things sometimes, so an all-in-one program.